Does Attending a Nine-Days Siyum Make Me A Bad Jew?

Every year the great Nine-Days machlokes grows stronger: To Siyum or Not to Siyum.

Frum-Twitter lights up with meat and memes, comedians weigh in, and Rabbanim address shaylos like “does Pirkei Avos count?” (All the while, of course, Sephardim are happily BBQ-ing on the front lawn.)

It certainly seems that people feel a guilty pleasure eating meat at a nine-days siyum. It feels disingenuous; a little sneaky. But then again, Yiddishkeit has all sorts of loopholes, right? After all, we all our sell Chametz, right? Why not enjoy a delicious steak dinner, so long as there's a little Torah thrown in? Enough people seems to be OK with it... so there's gotta be some opinion that says that this is allowed, even if it's not ideal, right?

Well... Not really, sort of. Maybe. Some background is needed.

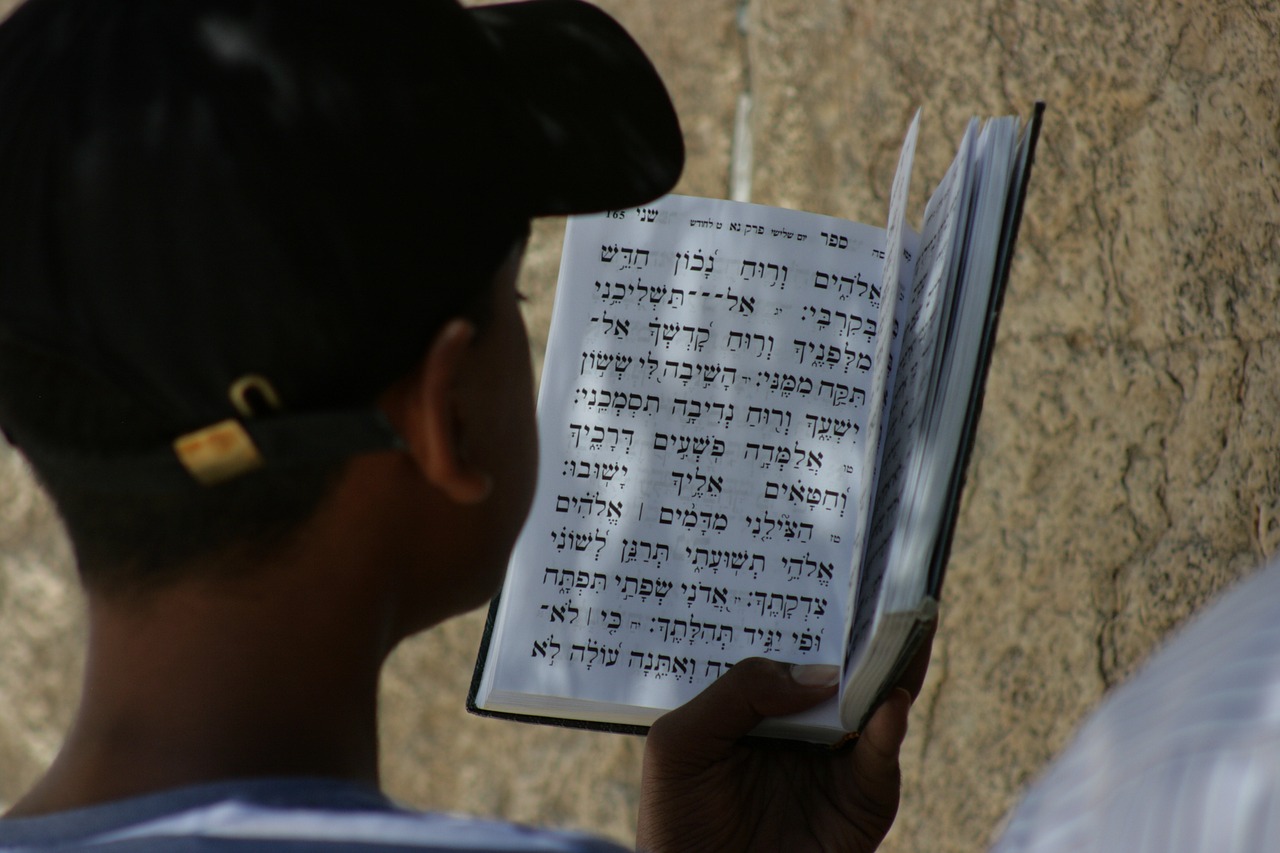

The Rama (ס׳ תקנ״א ס”י) does allow for the eating of meat at a Siyum, but restricts the attendees to those who are “Shayach” to the Siyum. During שבוע שחל בו ת״ב, the week in which Tisha B'Av falls out (and when Sephardim also refrain from meat and wine) the guest list is further limited.

The Mishna Berura (ס׳ תקנ״א ס״ק ע״ג) adds that one should certainly not speed up or slow down a regular schedule of learning to make such a Siyum, but that if it happens to work out that you finish during the nine days, and you usually make a Siyum, then you may invite the guests that you would usually invite.

There are many more nuances and subtleties to discuss, but this is the mainstream approach of standard, straightforward Halacha. Of course, there are many justifications offered for more expansive understandings of the how's, who's and when's of a Siyum. Some note that the definition of “usually” is dependent on time and location, and that during the summer at camps and on vacation, people have larger gatherings in general. Others point to the value of increasing Ahavas Yisrael and Talmud Torah. (Rabbi Gavriel Zinner lists many more in the footnotes of נטעי גבריאל הל׳ בין המצרים ח״א פרק מא).

But far beyond the questions of technical permissibility, there are deeper question of appropriateness. Does eating meat at a nine-days siyum subvert the spirit-of-the-law? The Aruch HaShulchan (תקנ״א כ״ג) certainly thought so, as he writes:

ודע שיש שמניחים הסיום מסכת על ימים אלו, כדי לאכול בשר. ודבר מכוער הוא And you should know that there are those who plan a Siyum in these days for the purpose of eating meat. This practice is despicable.

He takes issue with the abandonment of communal customs, the totally disregard for mourning over the Destruction of the Beis HaMikdash and goes so far as to question our ability and desire to control our base urges, explaining:

איך לא נבוש ולא נכלם? הלא הרבה מהאומות שאין אוכלים הרבה שבועות לא בשר, ולא חלב, ולא ביצים; ואנחנו עם בני ישראל, שעלינו נאמר “קדושים תהיו” – לא יאבו לעצור את עצמם שמונה ימים בשנה, לזכרון בית קדשינו ותפארתינו? How are we not ashamed? Is it not true that many of the nations of the world have many weeks where they refrain from meat, milk and eggs? And we, the Jewish People, about whom the Torah says “You shall be Holy” are not capable of holding ourselves back for eight days in the year in memory of the Beis HaMikdash?!

His mussar is well taken. If his generations over a century ago were getting too hedonistic, I think we're in trouble.

A friend and colleague recently noted to me that there is a basic theme behind so many of the questions he is asked in Halacha. They reduce to a simple request: “How can I live the unrestricted, pleasure-filled life that I want to live, and still feel like I'm keeping Halacha?”

Perhaps that take is overly cynical, but there is a painful truth to recognize. We desperately want to ensure that Halacha does not interfere with our lives, and this Yetzer Hara is easy to understand.

For starters, the concept of being an Eved Hashem is foreign in Western Society, and we are culturally conditioned to reject restrictions and authority. Holding back from a desired menu choice for religious purposes is about as un-American as it gets. That's true year 'round regarding Kashrus.

During the nine-days, however, the emotional requirement is far worse. This week we are asked to restrict ourselves for the expressed purpose of reducing our happiness. All of this is to focus on the loss of our Ancient Spiritual and Cultural Center two millennia ago. Simply stated: There is nothing here that resonates as a value in contemporary western society at all.

This is the battle that we (and the Aruch HaShulchan), are fighting in general. We are fighting it for ourselves, our kids and the future of Torah Judaism. This issue is the front line of ensuring the relevance and continuity of Torah values for ourselves and our future generations.

It seems then, that while there might be technical loopholes to arrange a “meat-eater siyum” there is no justification to utilize these loopholes outside of extenuating circumstances.

But perhaps there is more to the story...

After Rabbi Meir Shapiro's untimely passing, Rabbi Aryeh Tzvi Frummer, known as The Kozhiglover Rav, was appointed to be the Rosh Yeshiva of Yeshivas Chachmei Lublin. Throughout his life and Sefarim, he attempted to find a “לימוד זכות” – a meritorious defense – for some of our more perplexing practices. As such, in his Sefer on the Parsha (ארץ צבי דברים תרפ״ה), he addresses our question, and takes up the defense of learning a Masechta and arranging a siyum for the exclusive purpose of eating meat in the nine days. He writes:

The Talmud (שבת פח ב׳) quotes Rava as saying:

לַמַּיְימִינִין בָּהּ סַמָּא דְחַיֵּי, לְמַשְׂמְאִילִים בָּהּ סַמָּא דְמוֹתָא. To those who are “right-wards” in their approach to Torah (and engage in its study with strength, good will, and sanctity) Torah is a potion of life, and to those who are “left-wards” in their approach to Torah, it is a potion of death.

The normative interpretation of this teaching echos what we have been discussing. If we are proper in our study of Torah, then Torah is the elixir of Life. But utilizing Torah to undermine and subvert Ratzon Hashem turns the Torah into a dangerous poison.

But the Sfas Emes (לקוטים פרשת וישב) understands Rava differently, in light of the Chazal's well known principle in Avodas Hashem (פסחים נ׳ ב׳):

דְּאָמַר רַב יְהוּדָה אָמַר רַב: לְעוֹלָם יַעֲסוֹק אָדָם בְּתוֹרָה וּמִצְוֹת אַף עַל פִּי שֶׁלֹּא לִשְׁמָהּ, שֶׁמִּתּוֹךְ שֶׁלֹּא לִשְׁמָהּ בָּא לִשְׁמָהּ. Rav Yehuda said that Rav said: A person should always engage in Torah study and performance of mitzvot, even if he does so not for their own sake. Through the performance of mitzvot not for their own sake, one gains understanding and comes to perform them for their own sake.

If this is true, that learning Torah with alterior motives is still positive, then how can the Torah ever be a poison?!

The Sfas Emes answers by re-explaining Rava: When we learn Torah ״לשמה״, for its own sake, then Torah is an elixir of Live, adding to the quality, profundity and beauty of our lives. But sometimes we engage in Torah for some other purpose. On such occasions, the Torah does not add to our lives, but still protects us from sickness, pain and death. Talmud Torah is always good. It is always positive. Done right, it adds life, but even when done wrong, it prevents death.

With this in mind the Kozhiglover explains: During this time of the year, when the darkness of the Churban is so overwhelming and and pain of exile is most palpable, we should encourage any and all Torah learning, even for the wrong reasons. Even if it's just for the purpose of enjoying a good steak.

The power of Torah is that it can hold back the darkness, and we need all the help we can get.

Who is right; The Aruch HaShulchan or the Kozhiglover? The choice that each of us make here probably says a lot about the way we look at the world in general. But allow me to offer my own understanding: It appears to me that both are true. We are living in a generation that is walking the tight rope from exile to redemption.

From this precarious precipice, it is possible to tumble into Western hedonism and lose ourselves to the rat race, where all we yearn for is endless power and pleasure. Fall in this direction and the values of Halacha, Jewish History and the Beis HaMikdash will fade tragically into obscurity.

But it is also possible for us to collapse into loneliness, doubt, despair and depression. Fall here, and we conclude that we are never truly deserving of pleasure, and certainly not of redemption. We are fakers, imposters and charlatans; barely a shadow of the greatness of yesteryear. Nothing we do will ever be good enough, nothing is meaningful enough, nothing is potent enough to turn the tide and change the world we live in.

There are days that I feel I need the Aruch HaShulchan, and days that I need the Kozhiglover. There are values to both approaches, as well as pitfalls, and I'm grateful that our Mesora is broad enough to help steer us straight.

Is there a way to have your steak and eat it? Perhaps.

If we learn to navigate this tight rope, with empathy, thoughtfulness and intellectual honesty, we might merit that Hashem should help us to ensure that the question is never relevant again.

In the words of Rebbe Yehuda HaNassi (מגילה ה׳ ב׳): הואיל ונדחה ידחה – Since Tisha B'Av is pushed off this Shabbos, it should be pushed off forever.